Robert Henri (pronounced "HEN rye"), 1865-1929, may be my favorite American artist. His paintings are stunning, of course -- reason enough to love any artist-- but it isn't just that. It's that Henri's artistic sensibilities -- his sense of what we are trying to do when we paint, and, by extension, how we should go about doing it -- are invariably spot on.

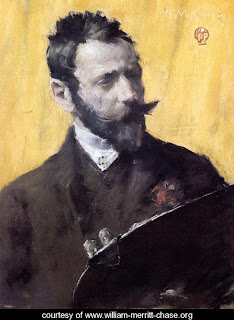

Robert Henri (pronounced "HEN rye"), 1865-1929, may be my favorite American artist. His paintings are stunning, of course -- reason enough to love any artist-- but it isn't just that. It's that Henri's artistic sensibilities -- his sense of what we are trying to do when we paint, and, by extension, how we should go about doing it -- are invariably spot on.If his rival William Merritt Chase (see earlier post) represented America's artistic establishment at the turn of the twentieth century, Henri was the iconoclast. For Henri, art was never simply about painting a "pretty picture." Henri wanted to capture the truth of, and search out the beauty in, everyday life. As a result his paintings frequently focus on commonplace, even conventionally ugly, things. Yet Henri somehow sees into and through his everyday subjects, managing to distill their essential beauty.

Henri was born on June 25, 1865 in Cincinnati, Ohio. In 1883 the family moved to New York City and then to Atlantic City, New Jersey, where Henri finished his first paintings. In 1886 he enrolled in the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts, where he studied under Thomas Anshutz. Two years later he traveled to Paris to study at the Academie Julian and embraced Impressionism. Later, he was admitted to the Ecole des Beaux Arts. At the end of 1891 he returned to Philadelphia and continued his studies at the Academy. In 1892 he began teaching at the Philadelphia School of Design for Women.

In Philadelphia, Henri attracted a group of followers who met at his studio to discuss art and culture, including some illustrators for the Philadelphia Press who would become famous as the "Philadelphia Four" -- William Glackens, George Luks, Everett Shinn and John French Sloan. While in Paris during this period, Canadian artist James Wilson Morrice introduced Henri to the practice of painting pochades on small, wooden panels (see earlier post). This method facilitates the rendering of the spontaneous, urban scenes for which Henri would become famous. Below, right, is Henri's Snow in New York, a well-known example of Henri's urban impressionism.

Henri began teaching at the New York School of Art in 1902, where his students included Edward Hopper, Rockwell Kent, George Bellows, Norman Raeben, Louis D. Fancher and Stuart Davis. In 1906 he was elected to the National Academy of Design, but when painters in his circle were rejected for the Academy's 1907 exhibition he accused fellow jurors of bias and walked off the jury, later referring to the Academy as a "cemetery of art."

In 1908 Henri organized a landmark show entitled "The Eight" at the Macbeth Gallery in New York. Besides his own works and those of the "Philadelphia Four," the show included paintings by Maurice Prendergast, Ernest Lawson and Arthur B. Davies. These painters and this exhibition would come to be associated with the "Ashcan School," an artistic movement that celebrated the beauty to be found in ordinary life.

Henri and his friend John French Sloan were great admirers of Walt Whitman and of Whitman's Leaves of Grass. Like Rembrandt and Dickens, they claimed, Whitman "found great things in the littlest things of life." Henri admired Rembrandt, Hals, Velazquez and Goya for their truthful rendition of the ordinary lives of human subjects.

Henri thought beauty could be found in ordinary life if seen by an extraordinary artist. The work of a number of Henri's students explores darker emotions. Many of Hopper's paintings, for example, are only coldly beautiful -- one senses a "love-hate" relationship between artist and subject. Henri was different: his paintings show a fond regard for the subjects portrayed. Henri loves his subject in spite of or even because of its ordinariness, or even its ugliness. (To understand this concept, think what it must be like to own and care for an English Bulldog.) Above, left, is Henri's Cumulus Clouds, East River, in which he reconciles urban life with a scene of stark, natural beauty. Classic Henri!

Henri thought beauty could be found in ordinary life if seen by an extraordinary artist. The work of a number of Henri's students explores darker emotions. Many of Hopper's paintings, for example, are only coldly beautiful -- one senses a "love-hate" relationship between artist and subject. Henri was different: his paintings show a fond regard for the subjects portrayed. Henri loves his subject in spite of or even because of its ordinariness, or even its ugliness. (To understand this concept, think what it must be like to own and care for an English Bulldog.) Above, left, is Henri's Cumulus Clouds, East River, in which he reconciles urban life with a scene of stark, natural beauty. Classic Henri! Henri's advice to his students is about the best I've seen anywhere, and I follow it (or at least try to follow it!) whenever I go out to paint. To achieve the direct transmission of self into art, Henri advised painters to work quickly on the entire painting surface rather than labor over individual parts. "Do it all in one sitting if you can. In one minute if you can." Most important, in Henri's view, art must be of its own time, based on subjects drawn from the artist's own experience -- and Henri thought that experience should be as wide as possible. Above, right, is Volendam Street Scene, in which Henri captures the simple elegance of everyday people going about their daily work.

In my last post I quipped that if you want to Channel William Merritt Chase, go to breakfast in the dining room of the Helmsley Park Lane hotel in New York, and gaze out the window at Central Park. You need no such elaborate prop to channel Robert Henri: to do it, just look out your back window and notice whatever is pleasing there that you hadn't noticed before. A good collection of Henri's work can be found online at The Athenaeum. Here's a link: http://www.the-athenaeum.org/art/by_artist.php?id=663

In my last post I quipped that if you want to Channel William Merritt Chase, go to breakfast in the dining room of the Helmsley Park Lane hotel in New York, and gaze out the window at Central Park. You need no such elaborate prop to channel Robert Henri: to do it, just look out your back window and notice whatever is pleasing there that you hadn't noticed before. A good collection of Henri's work can be found online at The Athenaeum. Here's a link: http://www.the-athenaeum.org/art/by_artist.php?id=663

One final note: Because of the focus of this blog I've been mainly concerned with Henri's landscapes and street scenes. As you will quickly see if you follow the link provided above, Henri painted a great many human subjects, as well, creating moving renditions of common people in everyday life. They are not to be missed!